How the Pandemic is Driving Commercial Building Energy Use

Months into the COVID-19 lockdown last year, positive headlines were few and far between. Among the limited uplifting topics to catch public attention, however, was sustainability. In December 2020, news outlets across the country wrote about data published in the journal “Earth System Science Data” that showed a 7 percent drop from fossil emission levels compared to 2019. That equates to an estimated 2.4 billion tonnes’ difference in CO2 emissions.

Turns out, all those drastic lifestyle changes imposed on much of the global workforce during lockdown may have wreaked havoc on the economy, but it did offer some — if temporary — relief to the planet. Emissions from transport accounted for the largest slice of the decrease.

Like most industries in 2020, commercial buildings underwent drastic changes during the pandemic. Restaurants closed. Big-box retail stores and small businesses alike sat empty. Much of the workforce vacated their offices, and many have not returned even a year later.

Unlike the transportation sector, however, commercial buildings’ greenhouse gas emissions during lockdown is harder to break down. In many cases, energy consumption in commercial buildings remained the same when it could have gone down, and in other cases, energy consumption even went up. Where energy consumption did go down, it was not proportionate to the occupancy drop.

This is a missed opportunity in the climate fight. Existing technology, such as the IoT-based Building Management System(BMS), can cut down operational costs in vacant or partially occupied buildings, and can even contribute to safer environments during a pandemic.

Buildings use a lot of energy, even in normal times

Commercial and residential buildings combined are the fourth-leading contributor to greenhouse gas emissions globally after electric power, transportation, and industry.

According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, these two sectors alone generated 565.8 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in direct emissions in 2015, or approximately 8.6 percent of total U.S. emissions. That percentage rises to 29 percent when use of off-site electricity generation comes into play.

What are commercial buildings doing to create all these emissions? About 30 percent comes from heating, cooling and ventilating spaces; 4 percent from water heating; 32 percent for cooking, appliances, electronics, and lighting; and 34 percent for miscellaneous factors such as data servers or ceiling fans. These different sources of energy use can help explain why commercial buildings saw an overall industry energy consumption drop of 11 percent between April and June 2020 compared to the previous year. Yet, buried within this statistic are trends that demonstrate an opportunity to correct wasteful energy use when buildings are unoccupied.

COVID-19 and the energy opportunity

Despite the overall 11 percent drop in energy use, overstressed hospitals saw a 600 percent increase in energy consumption. Perhaps this statistic isn’t all that surprising.

Empty office buildings during lockdown continued to guzzle energy to the tune of 40 to 100 percent of normal operation, despite 50 percent of the U.S. working population working from home.

Let’s take a closer look at that work-from-home statistic. According to Kastle Systems — a security company whose building access controls keeps track of FOB swipes — office occupancy plummeted from close to 100 percent in March 2020 down to between 10 and 25 percent, depending on the city. Since then, that number has struggled to break above 40 percent occupancy. Note that the Kastle Systems data measures individual building occupancy, not the percentage of workers back in their office nationwide.

This means that although office building occupancy has been historically low for the last year, office buildings’ reduction in energy use does not match. While building employees aren’t around to turn on the lights anymore, many commercial buildings continue to heat, cool, and ventilate.

Facility managers without HVAC controls or an IoT-based BMS may have struggled to remedy this because of the lack of remote-control capabilities and manual labor involved in tweaking their systems. With an IoT-based BMS, however, facility managers can put their entire portfolio of buildings into setback mode, ensuring none of their buildings are damaged from extreme temperatures, but aren’t wasting energy on occupant comfort standards.

The Department of Energy estimates savings of about 1 percent for each degree of thermostat adjustment per eight hours and recommends turning thermostats back 7 to 10 degrees from their normal settings for eight hours per day to achieve annual savings of up to 10 percent. Buildings in setback for an additional eight hours per day could achieve 20 percent savings in HVAC costs.

A building doesn’t need to be completely empty for the energy savings potential of building technology to apply. In the case of partial occupancy, facility managers can place unoccupied building zones, such as rarely used conference rooms, into setback, but keep occupied zones under normal operation.

Healthy buildings and energy consumption

As experts gain more knowledge about how COVID-19 spreads, it becomes increasingly clear that building systems have a role to play in mitigating indoor infections. Recommended strategies to decrease risk range from UV lights and bipolar ionization to filtration and ventilation, and these steps all have their own implications for building energy use.

Perhaps the most effective of these recommendations is increased outdoor air (OA) ventilation. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends this strategy to help dilute the viral load indoors and building operators can enact it simply by opening windows and doors. However, it’s not always possible to do this — schools and offices with windows that don’t open and poor weather conditions make it hard to achieve year round. Additionally, it’s not very effective if there’s no breeze. The other way to increase OA ventilation is to open up an HVAC system’s OA dampers as far as equipment capacity and the weather will allow. The American Society for Heating, Refrigerating and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) has a complete guide that facility managers can reference for this.

However, increasing OA ventilation comes with its own fair share of complications. Most HVAC equipment is not sized to handle all that extra outside air, so incorrect technique can cause equipment damage. Manually implementing this across a portfolio of buildings is labor intensive. Furthermore, extreme weather in hot and cold climates will mean an HVAC system will have to use more energy to treat air for acceptable indoor use.

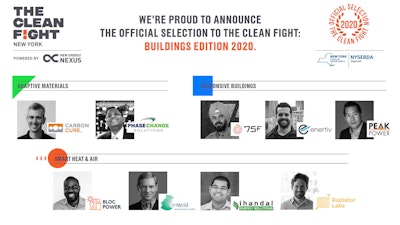

Where an IoT-based BMS is useful in cutting energy costs in empty buildings, so too can it help building owners looking to improve OA ventilation in their space and not suffer skyrocketing energy bills. 75F’s Epidemic Mode, for example, is a custom HVAC control sequence that automatically enacts CDC and ASHRAE guidelines for ventilation without any manual intervention required.

The significance of this goes beyond convenience, as the application molds itself to equipment types to avoid long-term damage and can also be tailored to partial occupancy schedules, meaning enhanced ventilation is only directed to occupied spaces. In a modeling study conducted by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), this strategy shows the potential to save building owners significant HVAC energy.

While commercial buildings have struggled to cut energy costs during the pandemic, existing technology has the potentially to easily improve the flexibility of building operations and pave the way for a healthier, more efficient future.